Branching vs. branchless add with data dependency

Branching vs. branchless add with data dependency

Introduction

Modern CPUs implement branch prediction to achieve massive performance gains, even when facing data dependencies that would otherwise expose the Von Neumann bottleneck. The weakness of branch prediction only becomes apparent in the relatively rare case where a condition in a hot loop is randomly determined and not overwhelmingly favoring a specific branch (>99%). In such cases, the solution can be a refactor to eliminate the branch, but branchless code comes with its own trade-offs.

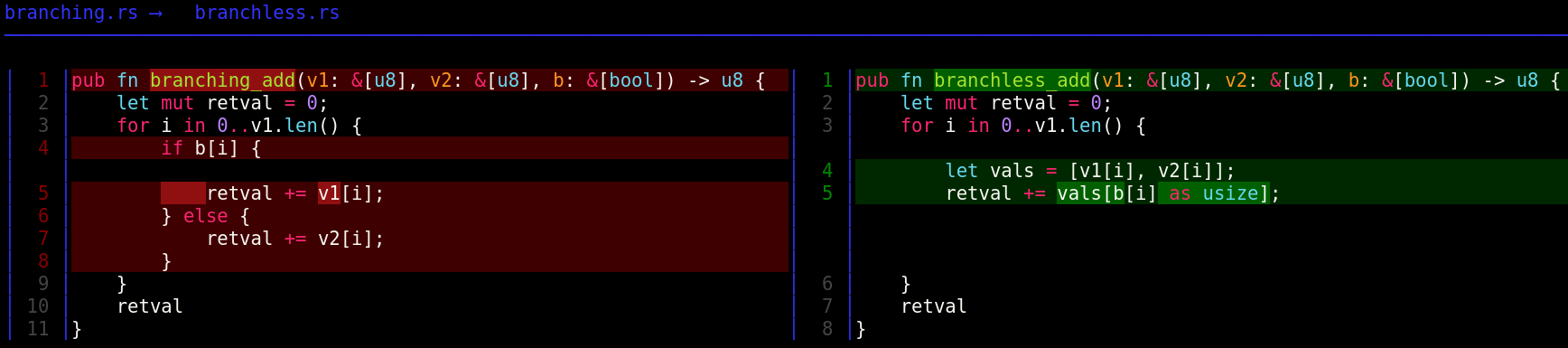

Comparing

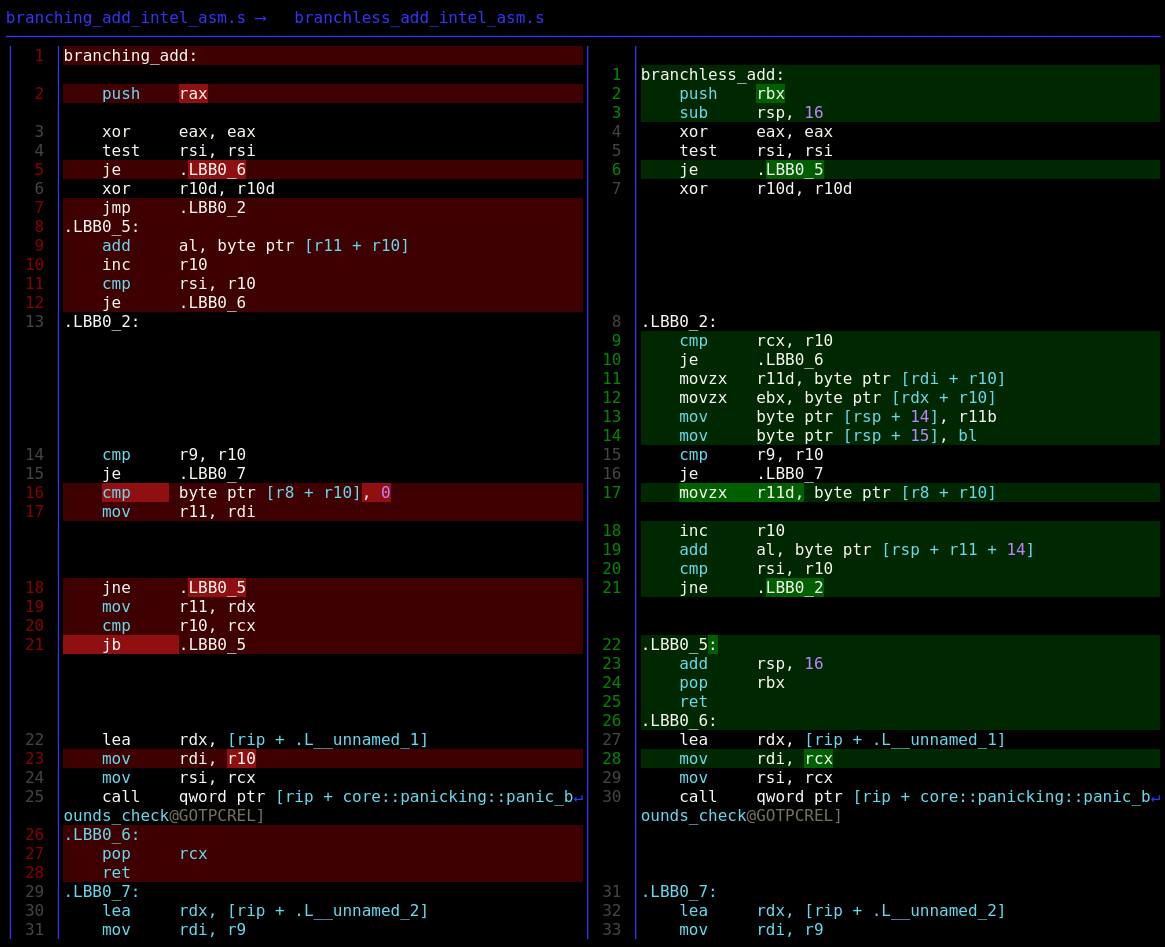

Assembly

Assembly Explanation

branching_add

First perform setup steps (function prologue) and test if the length of v1 is zero, in which case early return.

; l. 2-5

push rax ; store rax on the stack to preserve it

xor eax, eax ; clear eax (32 LSB of rax, which is retval)

test rsi, rsi ; if rsi is 0: goto LBB0_6 (rsi stores the length of v1)

je .LBB0_6 If rsi (length of v1) is not 0 continue.

; l. 6-7

xor r10d, r10d ; clear r10d (loop counter)

jmp .LBB0_2 ; goto LBB0_2Some more length checking (bounds checking), this time on b.

; l. 13-15

.LBB0_2:

cmp r9, r10 ; compare length of b with loop counter

je .LBB0_7 ; goto LBB0_7 if they are equal Now check whether to add v1 or v2 to the final result, and more bounds checking.

; l. 16-25

cmp byte ptr [r8 + r10], 0 ; if b[i] is false (base address of b + loop counter == 0)

mov r11, rdi ; move the base address of v1 into r11

jne .LBB0_5 ; jump if b[i] is true (not equal 0)

mov r11, rdx ; move the base address of v2 into r11

cmp r10, rcx ; compare loop counter with length of v2

jb .LBB0_5 ; goto LBB0_5 if loop counter is less

; v2 failed bounds check

mov rdi, r10 ; move loop counter (index value) into 1st argument

mov rsi, rcx ; move v2 base address into 2nd argument

call qword ptr [rip + core::panicking::panic_bounds_check@GOTPCREL] ; call error routineAt this point either the base address of v1 or v2 is stored in r11. So with the loop counter r10 as the offset, the i’th element of r11 is added to rax and a check if the loop counter matches the length of v1 is performed, which would mean the end of the loop.

; l. 8-12

.LBB0_5:

add al, byte ptr [r11 + r10] ; add the value at the address of r11 + r10 to the 8 LSB of rax

inc r10 ; increment loop counter

cmp rsi, r10 ; compare length of v1 with the loop counter

je .LBB0_6 ; goto LBB0_6 if they are equalLBB0_7 is entered if a bounds check failed on b and debug information is provided to the error routine.

; l. 29-33

.LBB0_7:

lea rdx, [rip + .L__unnamed_2] ; load address of a string (error message) into the 3rd argument

mov rdi, r9 ; move length of b into 1st argument

mov rsi, r9 ; move length of b into 2nd argument

call qword ptr [rip + core::panicking::panic_bounds_check@GOTPCREL] ; call error routineThis is the function epilogue that marks the end of a successful call to branching_add. This is called regardless of the length of v1.

; l. 26-28

.LBB0_6:

pop rcx ; pop/restore value of rcx

ret ; return from the functionSimplified branching_add

If we ignore function prologue, epilogue, error handling, and early returns on a zero-length v1, we can focus on the expected happy path which looks as follows:

; l. 16-21

cmp byte ptr [r8 + r10], 0 ; compare b[r10] == 0

mov r11, rdi ; move address of v2 into r11

jne .LBB0_5 ; if b[r10] == 0: goto to LBB0_5

mov r11, rdx ; move address of v1 into r11

; [...]

jb .LBB0_5 ; goto to LBB0_5; l. 9-12

.LBB0_5:

add al, byte ptr [r11 + r10] ; al += r11[r10]

inc r10 ; ++r10

cmp rsi, r10 ; v1.len() == r10

je .LBB0_6 ; if v1.len() == r10: we're donebranchless_add

Function prologue includes allocating stack space for the 2 element vals array, clearing return value register, checking if v1 has length of zero (early return) and clearing the loop counter register.

; l. 2-7

push rbx ; preserve value of rbx

sub rsp, 16 ; decrease stack pointer by 16 bits for the vals array

xor eax, eax ; clear eax

test rsi, rsi ; test if length of v1 is 0

je .LBB0_5 ; if length of v1 is 0 goto LBB0_5

xor r10d, r10d ; clear r10d (loop counter)Now entering the body of the loop, starting with a bounds check on v2. This is where the branching is erased by loading both the values of v1[r10] and v2[r10] and using the value of b[r10] to calculate the offset when performing the add to al

; l. 8-21

.LBB0_2:

cmp rcx, r10 ; bounds check on v2

je .LBB0_6 ; goto LBB0_6 if length of v2 equals loop counter

movzx r11d, byte ptr [rdi + r10] ; move v1[r10] into the 32 LSB of r11 and zero extend it.

movzx ebx, byte ptr [rdx + r10] ; move v2[r10] into the 32 LSB of ebx and zero extend it.

mov byte ptr [rsp + 14], r11b ; move the 8 LSB of r11 onto the stack at stack pointer (rsp) + 14

mov byte ptr [rsp + 15], bl ; move the 8 LSB of ebx onto the stack at stack pointer (rsp) + 15

cmp r9, r10 ; compare length of b with loop counter

je .LBB0_7 ; goto LBB0_7 if they are equal

movzx r11d, byte ptr [r8 + r10] ; move value of b[r10] into 32 LSB of r11

inc r10 ; increment loop counter

add al, byte ptr [rsp + r11 + 14] ; add value at stack pointer (rsp) + 14 + r11 to 8 LSB of rax

cmp rsi, r10 ; compare length of v1 to loop counter

jne .LBB0_2 ; goto LBB0_2 if they are not equalThe function epilogue deallocates the stack space for the vals array and restores rbx before returning.

; l. 22-25

.LBB0_5:

add rsp, 16 ; Deallocate the stack space for the vals array

pop rbx ; cleanup

ret ; returnFinally there’s error sections for a failed bounds check on v2 and b respectively.

LBB0_6 is called if the bounds check fails on v2.

; l. 26-30

.LBB0_6:

lea rdx, [rip + .L__unnamed_1] ; load address of a string (error message) into the 3rd argument

mov rdi, rcx ; move length of v2 into 1st argument

mov rsi, rcx ; move length of v2 into 2nd argument

call qword ptr [rip + core::panicking::panic_bounds_check@GOTPCREL] ; call error routineLBB0_7 is entered if a bounds check failed on b and debug information is provided to the error routine.

; l. 31-35

.LBB0_7:

lea rdx, [rip + .L__unnamed_2] ; load address of a string (error message) into the 3rd argument

mov rdi, r9 ; move length of b into 1st argument

mov rsi, r9 ; move length of b into 2nd argument

call qword ptr [rip + core::panicking::panic_bounds_check@GOTPCREL] ; call error routineSimplified branchless_add

If we ignore function prologue, epilogue, error handling, and early returns on a zero-length v1, we can focus on the expected happy path which is simply setting eax (retval) to zero and going through the loop.

The loop starts by implementing line 4 from the branchless_add:

let vals = [v1[i], v2[i]];as seen here (bounds check instructions replaced by […]):

; l. 8-14

.LBB0_2:

; [...]

; [...]

movzx r11d, byte ptr [rdi + r10] ; move v1[r10] into the 32 LSB of r11 and zero extend it.

movzx ebx, byte ptr [rdx + r10] ; move v2[r10] into the 32 LSB of ebx and zero extend it.

mov byte ptr [rsp + 14], r11b ; move the 8 LSB of r11 onto the stack at stack pointer (rsp) + 14

mov byte ptr [rsp + 15], bl ; move the 8 LSB of ebx onto the stack at stack pointer (rsp) + 15Then line 5:

retval += vals[b[i] as usize];is implemented as follows:

; l. 15-19

; [...]

; [...]

movzx r11d, byte ptr [r8 + r10] ; move value of b[r10] into 32 LSB of r11

inc r10 ; increment loop counter

add al, byte ptr [rsp + r11 + 14] ; add value at stack pointer (rsp) + 14 + r11 to 8 LSB of rax Finally the condition for jumping to the start of the loop or continuing to the epilogue is the equality of the loop counter and the length of v1.

cmp rsi, r10 ; compare length of v1 to loop counter

jne .LBB0_2 ; goto LBB0_2 if they are not equalLLVM Machine Code Analysis

The analysis is performed by first generating AT&T style assembly: feeding each set of instructions into llvm-mca

cargo rustc --release -- --target x86_64-unknown-linux-gnu --emit asmThen saving the relevant assembly from the output and feeding it into llvm-mca

cat ./asm/branching_add_at_asm.s | llvm-mca --resource-pressure=0 --instruction-info=0 --mtriple=x86_64-unknown-linux-gnu -mcpu=alderlake > ./mca/branchless_mca_summary.txt

Dividing instructions and cycles with the iterations gets us:

Branching |

Branchless |

|

|---|---|---|

| Instructions | 28 | 30 |

| Total Cycles | 9.08 | 10.03 |

So there’s more instructions and it takes more CPU cycles to go through the Branchless scenario, that’s not suprising but what does the trade-off of removing the branching mean?

Benchmarking with perf stat

The rust-perf-comp project was used to carry out benchmarks and gather statistics about each run.

The values of the vectors v1, v2, and b, were randomly determined and the benchmarks were carried out with various ratios of true/false values in the b vector. The randomness of the b values defeats the branch predictor’s ability to detect a pattern, and the varying ratios lets us examine the result of varying degrees of branch misprediction ratios.

The measurements of numbers of CPU instructions can be seen in the graph below.

CPU coreis the name of the standard micro-architecture for intel CPUs, whileCPU atomis the low power micro-architecture.

While there appears to be a lot of noise in the data, it is clear that branching requires more total CPU instructions when the ratio is nearer 50/50 which is where the highest degree of branch mispredictions is seen. The branchless implementation is much more stable but produces more instructions in the extremeties where the ratio is 100% true or 100% false.

Timing measurements and percent of branch misses are depicted below.

The cost of branch misses is very clear in the timing measurements, at worst the branching code is 7x slower while the branchless implementation is very stable around 500-600 ms. However we see that the branching code beats the branchless in the extremeties again.

Conclusion

Writing code with a high degree of branching does not rule out highly efficient code, due to the nature of modern CPU architectures with advanced branch prediction capabilities. There is however scenarios where branching code incurs a significant performance penalty, these scenarios can be resolved by refactoring branching to branchless code. It is important to measure before and after refactoring to branchless code as it is not a pure win, there’s a trade-off and without measuring there’s a risk of introducing a performance regression instead of an improvement.